Can Art Still Shock? - Guardian

|

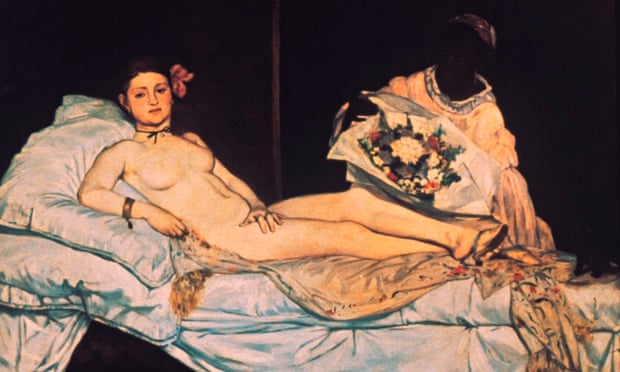

| "Shocking" was the word used to describe Edouard Manet's masterpiece when it was first unveiled in Paris in 1865. Olympia and the controversy surrounding what is perhaps the most famous nude of the nineteenth-century |

I was nostalgic because it seemed to me that shock was no longer possible. Or, perhaps more precisely, shock was no longer admissible. We are all, pronouncedGrayson Perry, bohemians now – and therefore unshockable by art. And if this is true, it signals a grand and maybe melancholy shift in the nature of art, and in the relation of art to society. It also appears to me – considering, let’s say, Pussy Riotand Ai Weiwei – a slightly provincial argument. And then came the attack on Charlie Hebdo.

Naturally, the discussion that followed was about the right to offend, and the potential geopolitical imbalances of such offence. But even more urgent it seems is to define what offence might be at all. To be shocking, to be offensive: the meaning of these noble terms might not be obvious. There are so many variants of shock. What might be necessary, for more precise orientation, is some kind of shock genealogy.

And the place to start, both symbolically and historically, is Paris.

Imagine that you are in 1865, at the Salon in Paris, looking at the paintings. You are, in this experiment with time travel, a critic. But you are not looking at the classical allegories with their cherubs and porpoises, or the sodden northern landscapes. Instead, you are laughing at a painting of a nude. The title of this painting is Olympia, and the artist isÉdouard Manet. Yes, here you are among the connoisseurs of shock – in the crammed atmosphere of Room M, listening to the way the critics talk among themselves. Olympia looks like a gorilla or monkey, they are saying, and the hand draped over her crotch looks like a spider or a claw. She is made of india rubber. Definitely she is unwashed, and the sooty marks of her cat’s paws can be seen all over her sheets. If, that is, anything can be made out at all: because really she is formless, inconceivable, a blur where there should be a body.

We are so used to the idea that the history of modernism represents a heroic succession of shock artists that it’s rather touching to observe how downcast Manet was by this reaction. He wrote a bedraggled letter to his friend Baudelaire: “I really would like you here, my dear Baudelaire; they are raining insults on me, I’ve never been led such a dance.” (To which Baudelaire admittedly replied in the full regalia of modernist panache: “What you ask from me is truly stupid. People are making fun of you; jokes annoy you; no one does you justice … Do you think you’re the first person to be placed in this position?”) But then, Manet wasn’t exaggerating. This painting, wrote critic and philosopher Georges Bataille, was “the first masterpiece before which the crowd fairly lost all control of itself”.

Now of course, to the innocent tourist in 2015 standing in front of this painting – which depicts a woman naked on a bed, her two companions a black woman bringing flowers, and a cat – such loss of control might just seem another episode from the history of 19th-century hysteria. But it is at least worth considering whether the contemporary critics were correct – not, perhaps, in how they theorised their reaction, but in having such a reaction. Not to be shocked at all might represent the greater obtuseness.

Sure, the scandal was to some degree purely to do with subject matter: that Manet had apparently so frankly depicted a prostitute. And some of it was to do with form: that Manet had apparently so frankly made his painting an exercise in sketched flatness. Those shocks were perhaps specific to the 19th-century atmosphere. But they were also just surface shocks. The deeper shock, as Bataille observed, was how no sign-system was useful in understanding Olympia. The painting could neither be defined according to “the drab world of naturalistic prose”, nor its opposite, the universe of “absurd academic fictions”. Manet’s genius and the true source of the bourgeois outrage was his ability to “disappoint expectation”: “instead of the theatrical forms expected of him, Manet offered up the starkness of ‘what we see’. And each time it so happened that the public’s frustrated expectation only redoubled the effect of shocked surprise produced by the picture.” The greatness of the art was that it changed the nature of the form. The shock was just a side effect.

Let Olympia, therefore, stand as a mini maquette of shock: the immediate improprieties of subject matter – prostitutes! The working classes! – followed by the more hidden improprieties of form. And yet none of this might be visible in the present moment. There’s a wonderful chapter in TJ Clark’s 1985 book The Painting of Modern Life, where he analyses the shock of Olympia, at the beginning of which he assembles the manic archive of contemporary criticism: all the chatter of the Salon virtuosi. The shock, he observes, simply created a failure of criticism. For in the present moment of outrage, there might be only absence, and frustration.

This creates one final, hidden complication: the more blankly frustrated a critic feels, the more she might also suspect that the entire operation was a deliberate joke. In a minor article on Olympia by a minor hack, A Bonnin, a rumour is reported that Manet’s painting was just “a parti pris on his part, a sort of ironic defiance hurled at the jury and the public”. (It’s true, Bonnin adds, that other people also tried to argue for Manet’s sincerity, but in the end no one could really know: “His canvases are too unfinished for us possibly to tell.”)

There’s something dubious about shock, something dirty and vulnerable to our purer disdain. Is shock anything other than a stunt tactic – an episode not from the history of art but of publicity? It’s that worry that lay behind the Salon chatter, and also the celebrated preface the Goncourt Brothers wrote, in the same year asOlympia, to their realist novel Germinie Lacerteux, where they posed the basic question: “Why have we written it? Is it just to shock the public and scandalise its tastes?” (Absolutely not, was the Goncourts’ noble answer. Their motives were entirely moral.)

Shock, it has to be admitted, is not chic. It is so often seen as juvenile, meretricious, boring. Even in 1865, shock was passé.

***

The heroic era of shock begins about a century earlier, with the Enlightenment writings of Voltaire, Diderot and co. The Enlightenment was a criminal publishing operation – their manuscripts so shocking that they had to be sent to Amsterdam to be printed and then smuggled back into France, hidden under straw in fish barrels or in the baggage of sympathetic diplomats. When the network failed, the consequences were gothic. Of one seizure, when three people were arrested, Diderot wrote to Sophie Volland: “They have been pilloried, flogged, and branded, and the apprentice has been condemned to nine years on the galleys, the colporteur to five years, and the woman to the hospital for her entire life.” By hospital he meant madhouse, in the future Soviet punishment style. In their novels and essays, Diderot and his accomplices were intent on dismantling the ruling ideology, and in particular the religio-political complex of the church and the state.

The Enlightenment was a renegade movement. In works such as Candide, or crazier excesses such as De Sade’s 120 Days of Sodom, all the ruling codes – political, sexual, semantic – are destabilised or rejected. (Edward Gibbon recorded one dinner he attended with the philosophes in 1763, where everyone “preached the tenets of Atheism with the bigotry of dogmatists, and damned all believers with ridicule and contempt”.) It’s the Enlightenment where the conjunction of art and shock began, and which is why 100 years later, by 1865, that conjunction was already suspect.

But one way of considering if our weariness is appropriate is to take a geographical sidestep. Yes, we might feel so over shock, in the liberal democracies, but it’s worth remembering the fate of shock in countries where the decor is less halcyon. One major heir of Diderot, for instance, is the feminist punk group Pussy Riot – put on trial for offending Russian Orthodox sensibilities after their brief performance, Mother of God, Chase Putin Out, in 2012 in the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour, in Moscow – of which the definitive study in English isMasha Gessen’s acidic book, Words Will Break Cement. Gessen offers the prehistory of Pussy Riot and their trial, including the art collective Voina – to which some Pussy Riot members belonged: “they wanted to confront a language of lies that had once been effectively confronted but had since been reconstructed and reinforced, discrediting the language of confrontation itself. There were no words left.” This was the problem Voina faced in the new era of Putin, which led to their happenings in supermarkets and subways – and it finds its retrospective analysis in the precise, restrained closing statements of the three members of Pussy Riot who were put on trial. As Nadya Tolokonnikova outlined it, these punk songs had a philosophical rationale: “We were seeking true sincerity and simplicity and we found them in the holy-fool aesthetic of punk performance.” just as the absurdist writers Daniil Kharms and Alexander Vvedensky confronted Soviet terror with nonsense poetry: “They paid with their lives to show that they had been right to believe that senselessness and lack of logic expressed their era best. They made art into history.”

If a work of art dismantles the ruling ideology, it will be intrinsically offensive to those who continue to believe that ideology. The legacy of the Enlightenment is this savage right to artistic offence, whose credo was summed up in Voltaire’s slogan: “I disagree with what you say but I will defend to the death your right to say it.” (Even if Voltaire was defending another Enlightenment hero, Helvétius, and never said those precise words.) And the “appeal of the Voltairean credo”, observed Tom Stoppard, soberly and correctly, “was precisely that it was voluntary, his choice. He was not conceding his antagonist’s possession of an overriding right, he was choosing to accord that right. He was putting down a marker for the kind of society he favoured, for an ideal.”

It is both the fragility and necessity of that ideal that was so brutally proved by the killings at Charlie Hebdo. While the cartoons for which they died prove a more complicated truth: that offence is a mobile category. Charlie Hebdo is a mini-Enlightenment publication, its hyperactive cartoons an expression of an absolute refusal politically of the ruling powers, and socially of religious belief. Just as in the notorious novel Thérèse Philosophe the Marquis d’Argens mocked the church’s pretensions to spiritual guidance, with his pornographic scenes where a priest inspires in a student ecstasies she maintains are purely metaphysical, so the cartoonists of Charlie Hebdo mock the Pope, or orthodox rabbis, or the madnesses of Islamism. But the Marquis d’Argens was only speaking to a local audience. Now, the audience is potentially global. The meaning of every work is therefore dependent on a much wider network of oppressions and ideologies. (One new problem of shock and new media is that so often it exists only as a rumour: a work can be freely condemned without being either seen or read.) And so the theorist Mahmood Mamdani can observe, defending the prosecution of cartoonists by the international tribunal into war crimes in Rwanda, that “we need to distinguish between bigotry and blasphemy. Blasphemy is the practice of questioning a tradition from within. In contrast, bigotry is an assault on that tradition from the outside.” But making that distinction in Rwanda is simpler than elsewhere. What is inside, and what is outside? If you see the Charlie Hebdo cartoons within a context of recent French internal politics, they may seem expressions of casual contempt. If you see them within a context of global militant Islam, they are expressions of courageous defiance.

***

On 11 May 1929, the writer Michel Leiris went to see Pablo Picasso. In Leiris’s journal, their conversation is summed up by the depressed sentence: “At present, there’s no means of making something pass as ugly or repulsive. Even shit is pretty.” To be nostalgic for the era of shock is a recurring malaise. But Picasso’s depression is the symptom of resistance. To make work that passes as ugly is one noble aim for art. Of course, outrage can be fleeting, and manufactured: there can be nothing more superficial than offence. But the usefulness of a small history of shock is to persuade one not to relinquish the concept of shock, but instead to examine it with more agility. And one possible future ideal may be not the fragile pleasures of ideological shock, however noble that may be, but to be shocking anthropologically.

In his book of open letters with Bernard-Henri Lévy, the French novelist Michel Houellebecq distinguished the art of the provocateur – someone who “calculates the phrase or attitude which will provoke in his interlocutor the maximum displeasure or discomfort; and then, rationally, applies the result of his calculation” – from his own novelist’s “form of perverse sincerity: I search obstinately, relentlessly, for the worst that might be inside me in order to lay it … at the feet of the public.” Like the Goncourts, he wanted to claim that there was nothing tactical in the possibility that his fiction might offend. Whether this is true, of course, is a problem of literary criticism. Houellebecq is a minor star of outrage – with each new work, there is a new accusation: racism, misogyny, and now, with his new novel, Soumission, Islamophobia. (In the week of the attacks on Charlie Hebdo, it was Houellebecq who was their cover star.)

And Soumission obeys so many of the usual shock tropes. Its background plot is already notorious – a rumour to be praised or excoriated. In 2022, thanks to a cynical sequence of political deals and machinations, France becomes an Islamic state. When a moderate Muslim Brotherhood party becomes increasingly popular in the polls, the two centrist parties become increasingly marginalised. To maintain a small amount of power, and to counter the far greater threat of a rising National Front, they both offer the Muslim party their support. And so its leader is elected president – and constructs a sketched version of Islamic government. To be a woman in this new world is a dismal prospect. But the economy stabilises, unemployment crashes, the family is a new utopia, and a new religious future seems to be offered to Europe.

But this fantasy is just a contraption for Houellebecq to pursue his true subject. The novel is narrated by a middle-aged male university professor, a specialist in the work ofJoris-Karl Huysmans, the 19th-century novelist who converted from aestheticism to Catholicism. His thesis on Huysmans was subtitled “The Exit from the Tunnel”, and it is a similar exit from a tunnel that Houellebecq’s novel describes. For as always in his novels, modern life is described – with wilful comic terror – as a dead landscape of circumscription and ennui: a desolation of microwave meals, bored sex and smoking bans. In this desolation, there are fleeting moments of hope – such as the love shown him by his Jewish girlfriend Myriam, who decides to emigrate. But the only lasting future hope is conversion. And so the novel ends with the narrator contemplating his future conversion to Islam, superficially for the material benefits (the university salary from Qatari funds; the multiple wives), but really because submission to God is the only way of recovering meaning given the shallowness of a liberal, western democracy. Only religion offers the prospect of “a second life” – even if that future, in the novel, remains hypothetical. Just as the epigraph to the novel, from Huysman’s En Route, describes the basic dilemma, as Huysmans’ narrator sits in the church of Saint-Sulpice, wondering if he can pray: “I am very much disgusted with my life, very much tired of myself, but there’s a long way from there to leading another existence!”

For Houellebecq is the novelist of the impasse. In a pre-publication interview, he stated his basic position: “The Enlightenment is dead, may it rest in peace.” This has been his philosophy throughout his career, and it is the source of his deeper affront against the entire project of secular, liberal progress, which is rejected in the melancholy of his prose. The apparent outrages to thesensibilities of others are masks for a greater outrage: an absolute philosophical pessimism, an intellectual ugliness …

***

And yet: I’m not sure that the example of Houellebecq is enough. The forms of his novels are always drably conventional – alternations of conversations and descriptions. Whereas, I keep thinking about Manet’s Olympia, and TJ Clark’s lovely observation that one source of the public’s confusion was a miniature shift: the way Olympia holds the viewer’s gaze, unlike the dreamy narcotised eyes of one of his models, Titian’s Venus of Urbino. That small shift represented a giant formal refusal – a formal shock that represented a rejection of social norms, too.

The truly shocking work, such as Pussy Riot’s punk prayer, will investigate the ideology of its own making. The future works of shock I imagine are as formally adventurous as they are intellectually destructive. I’m not in fact sure that true resistance to ideology is possible without resisting aesthetic conventions. The new shock moves might well be quieter, more low‑rent – in the invention of new forms that are troublesome, and mischievous. A quick list for consultation might include the monologues of Wallace Shawn, such as his great piece The Fever, with its direct address to the complicit audience; or the giant length of Roberto Bolaño’s novel 2066, with its meticulously comprehensive descriptions of the murders of hundreds of women in Santa Teresa; or the experiments in curatorial choreography of the artist Philippe Parreno. In other words, one path for investigation might be to disturb the usual compact of distance between the writer and the reader, or the performance and the audience.

The future art work can be as quiet as it likes in the way it shocks. I would just like to make sure that it survives.

• Adam Thirlwell’s latest book Lurid & Cute is published by Jonathan Cape.

Comments

Post a Comment